200 million euros in property damage, dyke breaches, destroyed harbours - the storm surge on 20 October 2023 was the worst for the Baltic Sea coast in 150 years. It was already clear a few days in advance that the coast would be hit hard. But why was the storm still able to cause so much damage? What is the situation today, one year after the flood?

The millennium flood of 1872 on the Baltic Sea

Storm surges are not uncommon in the north, although in most cases they affect the North Sea coast. As the low-pressure areas in our latitudes are usually accompanied by south-westerly or westerly winds, storm surges in the Baltic Sea are much rarer. A look at the data from the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) shows that very severe storm surges with a water level of more than two metres above mean sea level (NMW) have only occurred three times in the last 150 years. The storm surge of 13 November 1872 with a water level of 3.30 metres above mean sea level and waves up to 5.5 metres high in the western Baltic Sea illustrates the violence that nature can unleash "on the Baltic Sea" - but it is still considered a millennium event.

Back in November 1872, strong south-westerly winds initially pushed the Baltic Sea water towards the Baltic. As a result, the German Baltic coast experienced a storm low tide with water levels of one metre below the NMW, which ensured that large quantities of water from the North Sea were drawn through the Belts into the Baltic Sea - the Baltic Sea was therefore overflowing. When the wind changed from south-west to north-east and developed into a two-day hurricane, the water from the eastern Baltic Sea sloshed back to the coasts of Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania as if in a bathtub. Combined with the strong winds, this caused catastrophic damage and the highest water levels since records began: Parts of Lübeck, Kiel, Eckernförde and Flensburg were metres under water, hundreds of people lost their lives and thousands were left homeless.

The underestimated flood?

Fortunately, it didn't get that bad in 2023, but the storm event on 20 October 2023 was the worst flood since 1872, although the general weather conditions were quite comparable: A powerful high had been hanging over northern Sweden for days and a storm depression was approaching from the south-west. As a result, an air mass boundary with large differences in temperature and pressure formed directly over the Baltic Sea - orange and red colours dominated the wind forecast charts days in advance, and coastal residents and boat owners were warned urgently in the media.

A strong easterly wind set in on the day before the forecast storm, 19 October. Forecasters reported 30 to 35 knots from the east to south-east for the Schleswig-Holstein Baltic coast that day. In view of the still mild temperatures, many windsurfers were out on the water between Rügen and Flensburg that day. It was noticeable: The actual wind was much stronger than forecast in many places.

The wind was much stronger than forecast

At the Danish spot Kegnæs, for example, the forecast was exceeded by five to ten knots, gusts of over 40 knots meant that sails between 3.0 and 3.7 m2 were already the order of the day in the early afternoon. Anyone who had planned to leave their smallest sail at home until the following day was left out in the cold.

But wasn't this all just the warm-up for the real storm the next day? "When we travelled down from Kegnæs that day, we already suspected that it could get pretty rough tomorrow," recalls Flensburg local Tom Eierding. "The waves and water level were already quite high and the big end wasn't due to come until a day later."

I only had three wave rides that day, but they were an experience." (Marcus Friedrich)

The storm intensified further over the course of 20 October. From Rügen to Flensburg, wind speeds of over 50 knots were constantly measured throughout the day, with gusts of over 70 knots. Marcus Friedrich, photographer and passionate windsurfer from Stralsund, was travelling on Rügen that day to look out for surfable spots and capture the event on film: "In Mukran on the east coast, the storm was pushing in flat onshore, with my 3.2 sail I would have had no chance here at all. So we explored the north coast and found what we were looking for in Kreptitz. The shore area was covered, but there were still two to three metre high sets rolling in and the wind was coming from offshore. It was difficult to get out at all, I only had three wave rides that day, but they were an experience," recalls Marcus Friedrich.

Logo-high waves at the flat water spot Stein

Further west, the measuring station at the Kiel lighthouse reported gusts of 65 knots. Nevertheless, some of the protagonists, including Leon Jamaer and Max Dröge, set off in search of rideable spots. Leon looks back: "Of course I had realised that it was going to be pretty rough, so I didn't want to travel far, but wanted to check out the spots on my doorstep. We went to Schönberg first, but the rock piers were already flooded there, which was too dangerous for us. So we thought about where there might be a spot that offered a bit of cover and found what we were looking for in Stein on the north-east shore of the Kiel Fjord.

Normally, this is a shallow lagoon where surfing students make their first attempts, but on this day, the high water level meant that logo-high waves were rolling over the offshore sandbank. With a 3.5 metre sail, it was halfway rideable for me and the waves were surprisingly smooth due to the sideoffshore wind. Looking back, I can't remember any better waves in the Kiel city area. It was only afterwards that we realised how bad it had been on more exposed beaches, which I hadn't expected," says Leon, describing his experiences that day.

It was only afterwards that we realised how bad it had been on some of the beaches." (Leon Jamaer)

A few locals, including Tom Eierding and Holger Beer, also tried to surf the storm in Kegnæs. Tom reports: "In the shore area it was somewhat covered, here you could still ride some waves with the 3.4 sail without being completely smashed. Further out it was a struggle. Around lunchtime, the wind was so strong that none of us could jibe any more. We crouched down in the water, had the sail folded and then set off in a new direction. At 2 p.m. it was finally over, as the causeway to the mainland was in danger of being flooded. When we were one of the last vehicles to cross over, the first waves were already crashing over the causeway. In view of the fact that the storm was set to get worse, this was worrying. The next morning we read that half of the dam and road had been torn away during the night."

Should you go surfing during storm surges?

The fact that some windsurfers took to the water even during the strongest storm floods in 150 years divided opinion. The comments ranged from respectful admiration to hostility on social media, along the lines of: "When people are fighting for their belongings, it's better to carry sandbags than post surfing photos."

Everyone has to decide for themselves where the limits of such activities lie. What is certain is that you should only go out on the water in extreme conditions if you have the necessary skills and plenty of experience. You should also realise that you have to assume that you are on your own in an emergency, as both the sea rescuers and the rescue services on land would probably have had more important things to do that day than rescue water sports enthusiasts in distress.

Ship cemeteries in Schilksee and Damp

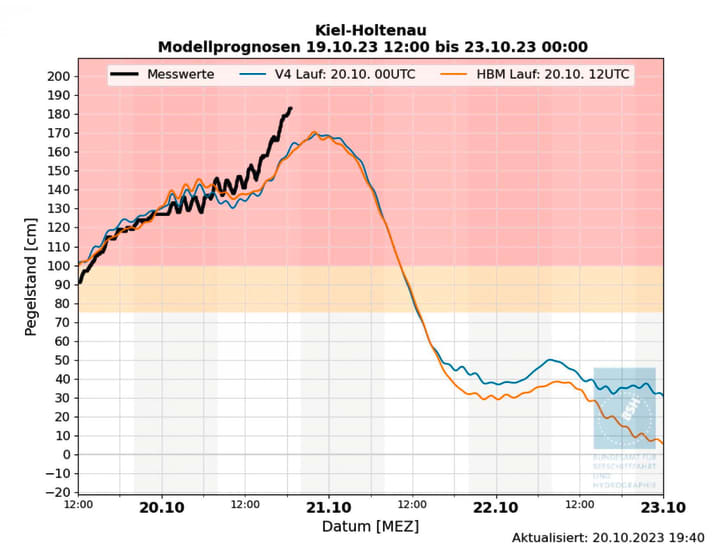

The fact that a state of emergency prevailed on many stretches of coast was also due to the fact that the storm surge was significantly higher than forecast by the models. In the Eckernförde Bay, the Baltic Sea rose to +2.10 metres above the mean sea level, in Flensburg even to +2.37 metres above the NMW - the highest value measured since the millennium flood of 1872. The consequences were correspondingly serious: beaches and dune belts were destroyed in many places, and several metres broke off the cliffs in some places. Many harbours between Flensburg and Lübeck were badly hit and presented an apocalyptic picture the morning after. In Damp and Kiel-Schilksee, the masts of dozens of sunken ships protruded from the water, parts of jetties and metre-long motor yachts lay on the quays.

Jan von der Bank, sailor and author, reported in the sister magazine YACHT late in the evening of the storm: "Kiel-Schilksee is like a ship graveyard. What happened here today was an apocalypse, the worst thing I have ever experienced in connection with sailing." Many campsites along the fjords were also flooded; in Waabs on the northern shore of Eckernförde Bay alone, the tide washed away 150 mobile homes. And even on the island of Rügen, where the storm surge was less severe, massive shoreline paths were simply torn away.

Tidy up, wash up, upgrade

The clean-up work began as soon as the storm subsided. Since then, the main focus has been on repairing the damaged sea defences and replenishing the washed away beaches, because: No beach, no tourists. After the storm, the holiday resort of Schönberger Strand near Kiel was symbolic of many other coastal communities: The fine sandy beach and dunes were history for several kilometres; instead, windsurfers now carried their equipment over the stony substructure of the land protection dyke into the water.

Mayor Peter Kokocinski explained in the Kieler Nachrichten newspaper after the storm event: "We lost around 30,000 cubic metres of sand over a length of several kilometres; there has never been so little sand here since the dyke was built in the 1980s."

Work to restore the beach in Schönberg began in spring 2024, with a pumping vessel moored off the coast for many weeks, transporting tonnes of sand and water mixture to the shore. Large parts of the beach were restored for the holiday season. However, it will be a long time before the beautiful belt of dunes that separated the beach from the dyke until a year ago is fully restored - unless a new storm surge strikes first and undoes all the efforts.

Also interesting:

Manuel Vogel

Editor surf

Manuel Vogel, born in 1981, lives in Kiel and learned to windsurf at the age of six at his father's surf school. In 1997, he completed his training as a windsurfing instructor and worked for over 15 years as a windsurfing instructor in various centers, at Kiel University sports and in the coaching team of the “Young Guns” freestyle camps. He has been part of the surf test team since 2003. After completing his teaching degree in 2013, he followed his heart and started as editor of surf magazine for the test and riding technique sections. Since 2021, he has also been active in wingfoiling - mainly at his home spots on the Baltic Sea or in the waves of Denmark.