Surfboard construction - as I understand it, this is filigree millimetre work, idealism that has become shape. And now I'm standing here, in a huge hall at Cobra, the world's largest board manufacturer. In front of me, a Thai employee is using an impact wrench to unscrew 2-euro-sized steel nuts from the bolts. Moulds swing from the forklift truck to their destination on heavy chains. In this part of the production facility, the material for the EPS cores is injected into moulds through thick hoses and expanded using heat. With all due respect, it doesn't look like delicate millimetre work here, more like heavy industry.

Cobra - early boom and crisis times

The story of Cobra began in 1977 in a small garage under a house in Bangkok. Three friends built their own boards there for their participation in the Siam Cup. They were Vorapant Chotikapanich and his partners Bert and Karl Morsbach. A year later, they founded Windglider Thailand and began building their first series boards, which became Cobra International in 1985. The mother of all fun sports boomed worldwide in the eighties and nineties, and as a result, several windsurfing board manufacturers emerged in Asia. At this time, Cobra was one of many - but clearly on a growth course, with the number of employees having long since reached three figures. However, the upswing was abruptly halted in 1987. The factory is working at full capacity, containers full of boards are on their way to Europe when it becomes clear: The boards were getting blisters! It was irreparable structural damage, presumably caused by trapped moisture or poor quality resin. This affects 90 per cent of the goods. Cobra is inundated with complaints, and in the end the boards are not even returned for inspection, but simply disposed of on the spot. Economically, this super disaster breaks Cobra's back and the banks are now breathing down the necks of the three entrepreneurs. Bert and Karl Morsbach had to leave Cobra, but Chotikapanich was allowed to stay - "probably primarily so that someone could keep the company running and pay off the debts at some point", surmises Danu Chotikapanich, son of the company founder and CEO of Cobra since 2005.

At this time, the damage to the company's image was just as severe as the economic loss. Cobra's return to growth was mainly due to new brands increasingly entering the market: Tabou Windsurfing was founded in 1991, followed by Quatro and Starboard in 1994 and finally JP-Australia in 1997. They all come to Cobra, because there is now a significant competitive advantage here: in Europe, boards were previously mainly built in aluminium moulds. These were so expensive and complex that a large number of units were required to amortise the moulding costs. Individual models therefore had to run for many years in order to be economically viable.

However, because the wheel of new brands, shape innovations and trends was turning ever faster, there was a need to be able to change shapes quickly. "The brands wanted to realise their own ideas without restrictions, bring new shapes and new designs onto the market," recalls Paolo Cecchetti, who has been responsible for innovative production processes at Cobra for many years. "Because Cobra was able to guarantee this by using more favourable composite moulds, more and more brands came to us to have their boards produced here." As a result, Cobra grew massively between 1995 and 2006, from 300 employees to over 5,000. But even this growth phase was not without its problems, because while the number of employees grew by a good 17 times, turnover did not keep pace.

"When I took over the company in 2005, we had as much debt as annual turnover," recalls CEO Danu Chotikapanich. "Everything had grown out of control, we were building for the windsurfing and surfing industry, as well as boats and car parts. Boards were stored in tents between the buildings, sanding work was sometimes carried out outdoors and the air was so full of sanding dust that you could barely see the neighbouring building. Each board passed through 50 hands on the factory site and was transported for kilometres from station to station, it was crazy. We had far too much stock here, and when the financial crisis hit in 2008, the house of cards collapsed. The banks wanted their money back, Cobra was insolvent again. What followed was another lost decade in which we had to painstakingly consolidate. Many processes were restructured and made more efficient, and the number of employees fell to around 2,200. Today, the production line for a windsurf board consists of just ten stations and we can call ourselves an economically healthy company," says Danu Chotikapanich, summarising the ups and downs at the time.

The air was so full of sanding dust that you could barely see the neighbouring building

What had been a problem at times in the past - Cobra's broad portfolio - actually became an advantage in the late 2010s. While sales figures in the windsurfing sector continued to decline, Cobra was able to compensate for this by producing surfboards, wingfoilboards, SUPs and now also e-foilboards. Today, 70 per cent of Cobra's turnover comes from the water sports sector, while 30 per cent is generated in the automotive sector, where special carbon parts for spoilers or bonnets with a carbon look are produced for manufacturers of expensive sports cars.

Shock waves

Just as Cobra had fought its way out of the crisis, the shockwaves of the coronavirus pandemic also hit the board manufacturer. Fuelled by travel restrictions and social distancing rules, people suddenly invested in new water sports equipment and, after years of overproduction and discount battles, boards were suddenly in short supply. Brands were ordering large quantities - shops were selling goods without discounts for the first time and production at Cobra was booming. The problem: too many manufacturers were blinded by the unexpected upswing and produced too many products. Because the boom subsided just as quickly as it had arrived, the industry was left sitting on products shortly afterwards and is still struggling with the effects today, as stocks have had to be pushed onto the market via massive discounts ever since.

According to Danu Chotikapanich, the fact that windsurf board sales are currently at an all-time low also has to do with a failed marketing strategy on the part of some manufacturers. Danu shows an old picture of Robby Naish cruising on a longboard: "Maybe we just need more of this and less racing, big wave, freestyle - simply less extreme. But I think a lot of brands still haven't got it." Bruce Wylie, 1984 Olympian on the windsurfer and now head of the windsurfing division at Cobra, echoes this sentiment: "At the moment, a lot of people are throwing themselves into wingfoiling. But you can't do this sport everywhere and you need a certain wind strength - wingsurfing is also a niche in this respect. But I also realise that there will always be people who love the feeling of riding a windsurf board across the water. In this respect, wingfoiling is certainly a current trend, but it's certainly not the end of windsurfing."

Core expertise at Cobra

Paolo Cecchetti takes me on a tour of the hallowed halls - and there are quite a few of them on the factory premises an hour east of Bangkok. No less than 14, to be precise - many two-storey high, each as big as a football pitch. Milling, laminating and sanding are carried out here. Paolo's business card reads "Chief Innovation Officer", meaning he is responsible for the technologies used to build the boards. Before joining Cobra in 2001, he was co-founder of the Italian brand Drops. It is now his job to develop and optimise the right layups, i.e. the structure of the boards, for the different requirements, ideally in close collaboration with the brand representatives. "I advise the shapers, for example, on which layup they can best achieve the desired requirements in terms of riding characteristics and stability - the final decision on the design is made by the brands. As a manufacturer, we have to take responsibility afterwards for ensuring that the agreed specifications have been adhered to and that reinforcements have been installed correctly. What is interesting for many manufacturers is that we at Cobra offer everything from a single source, from manufacturing the EPS cores and laminating the boards to the fin and straps. We even make the plastic plugs for the straps or the pads ourselves," explains Paolo with pride.

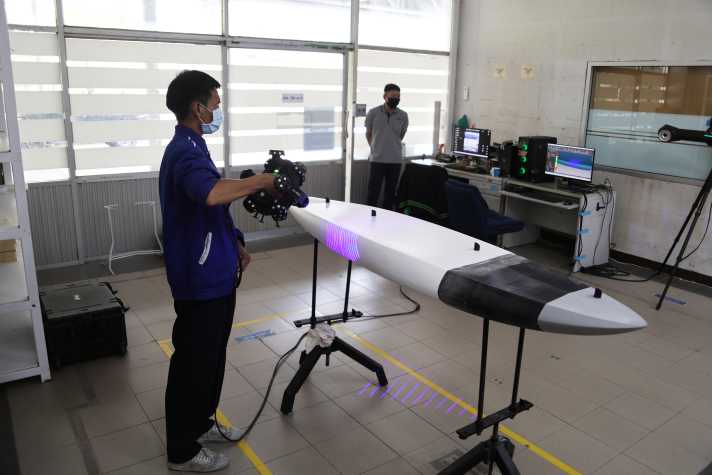

Paolo opens the door to the "scanning room", a tiled room with all kinds of technology. The prototype approved by the shaper is imaged here using a 3D scanner, and a three-dimensional image of the shape, with all the details, is created on the computer in real time. A suitable EPS core is then produced based on the planned design. If it is a team rider board that is being produced in very small quantities, a CNC milling machine mills the core out of a block. For models that are built in larger quantities, a core mould is usually produced from which the cores come out directly to fit, which saves milling work, material and therefore costs. "The core," explains Paolo, "is super important because it has a significant influence on weight and stability. Generally speaking, the denser and finer-pored the core material, the more pressure-resistant it is, but also the heavier it is - and vice versa. We have now developed a new core, Dual Fusion Core called. This consists of very light EPS material on the inside and has an extremely pressure-resistant and dense edge on the outside. This technology therefore combines both advantages: light weight and high pressure stability. This is already being used for downwind boards and wingfoil boards, and may soon be used for windsurf boards too. This opens up new possibilities for brands. For example, a denser, but also more pressure-resistant core can be selected, which can then be equipped with less laminate under certain circumstances."

Blowing the EPS material into the core moulds is certainly the work step that looks most like heavy industry: After injection, the core bakes in the mould, the halves of which are held together by numerous screw clamps, steaming and hissing everywhere. After around 20 minutes, the work step is completed, the upper part of the mould is pulled up on chains and out comes an EPS core that is already very close to the original in terms of its shape - and which, above all, can be reproduced up to 500 times. The mould construction method also guarantees that less waste is produced than when cores are milled from blocks. Conversely, this also means that a core mould is stored on the factory premises for each size of each model, which is then also available for any subsequent productions in the coming years. These are stored in endless rows between the halls.

From Inside Out to Single Shot

Terms such as "inside out" or "single shot" may sound like sushi or a wet party, but they actually refer to what happens after the cores are manufactured. This is because manufacturers have several options for applying the laminate, i.e. sandwich panels, glass fibre or carbon fabric, to the core.

In the single-shot process, the core and the individual carbon and reinforcement layers move into a second mould and are "baked" in a single step. To ensure that the employees know exactly where the individual layers need to be positioned, there are "tech sheets", records with the exact specifications. The process is more complex with the "press mould", a second mould that is used to bond inserts for the mast track, straps and fin boxes as well as the sandwich panels and reinforcements - such as wood or carbon patches in the standing area - to the core. The advantage of this moulded construction method: Little reworking and levelling is required, as accuracy and reproducibility are extremely high. Once this blank comes out of the mould, the cover laminate, i.e. large carbon or glass fibre layers, are applied to it in a further step.

Today, the production process for windsurf boards consists of just ten steps

The third option, the "semi-custom process", is mainly used for team rider boards, i.e. boards in small quantities for which it is not worth building a second mould. Here, the board is built "inside out", from the inside out, in individual steps.

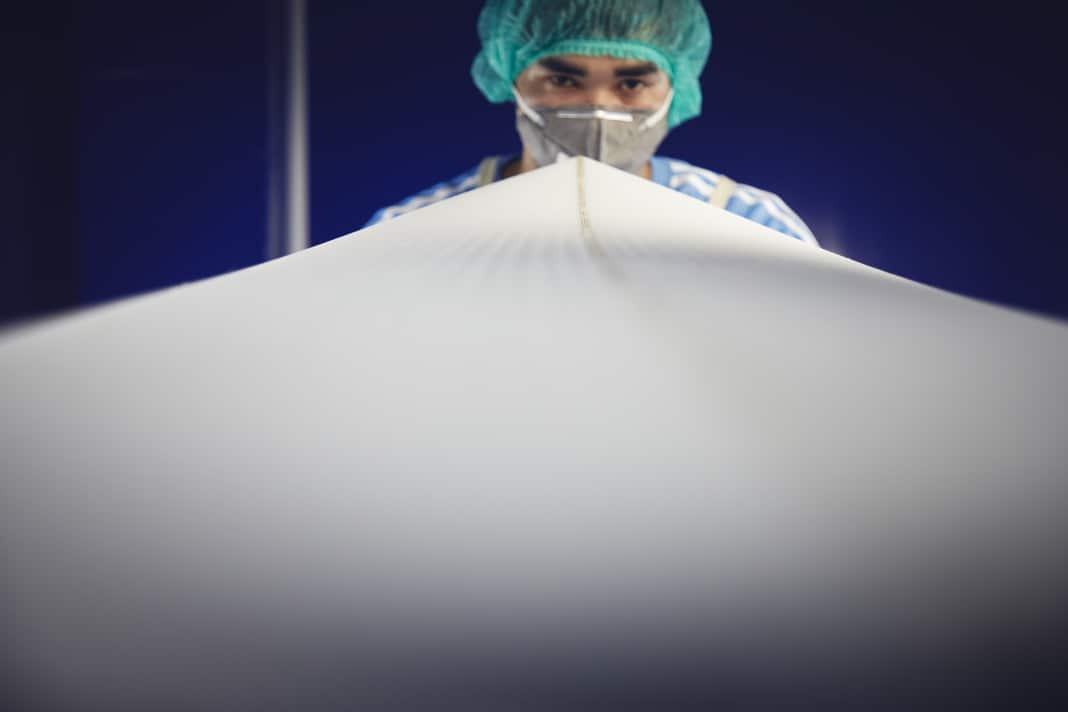

When it comes to Asian production, many people have images of dilapidated halls and poor working conditions in their heads. However, all employees, mainly from Thailand and Cambodia, wear appropriate protective clothing and respiratory protection, and there are extraction systems in the sanding and painting rooms. To combat the Thai heat, there are countless fans distributed throughout the production halls. These are also necessary, as the thermometer shows 37 degrees in the shade during our visit. And a lot is also happening when it comes to sustainability: around 50 per cent of the energy required now comes from the company's own roof, and the halls are extensively covered with photovoltaic systems. By 2030, all the energy required for the production process is to come from renewable sources, making the manufacturing process CO2-neutral. "Green boards are still a long way off," says CEO Danu Chotikapanich, "even if the companies sometimes present it a little differently. Bio-resin and wood inserts are a good thing in principle, but ultimately a surfboard is a composite product that cannot simply be composted or separated and partially recycled. On a sustainability scale from 0 to 100, we are at 5."

Trust is good, control is better

Quality control is provided for all work steps on the production line. For this purpose, there is a bundle of templates approved by the shaper for each board, which can be used to check at certain reference points whether, for example, the underwater hull or the rounding of the edges fit. The weight of the board is also determined after each work step so that any deviations can be recognised in good time. Once the boards have been fitted with pads, painted and polished, a final function test is carried out. In other words, all fin boxes and mast tracks are checked to ensure that the fin plates and base plates can be inserted without any problems. A slight overpressure is applied to the ventilation valve with compressed air - the employees can then see if there are any leaks in the mast track or loop plugs by sprinkling a little soapy water on them. If the boards also pass this final check, they are packed and leave the factory - ideally to make a windsurfing dream come true somewhere in the world.

Also interesting:

Manuel Vogel

Editor surf

Manuel Vogel, born in 1981, lives in Kiel and learned to windsurf at the age of six at his father's surf school. In 1997, he completed his training as a windsurfing instructor and worked for over 15 years as a windsurfing instructor in various centers, at Kiel University sports and in the coaching team of the “Young Guns” freestyle camps. He has been part of the surf test team since 2003. After completing his teaching degree in 2013, he followed his heart and started as editor of surf magazine for the test and riding technique sections. Since 2021, he has also been active in wingfoiling - mainly at his home spots on the Baltic Sea or in the waves of Denmark.