Sometimes they are small and an hour old, sometimes huge and have travelled thousands of kilometres before we are lucky enough to accompany them on their last few metres to shore. But these few seconds are enough to turn us into different people. The energy, majesty and sometimes the elemental force of waves is absolutely fascinating.

No wave spot in the world is like any other - wind, tides, swell and the bottom always require you to adapt to each spot anew - that is also part of the fascination. On the one hand, this means that wave riding never gets boring, but on the other hand it also means that it takes a lot of experience and practice to get along well in a wide variety of conditions. Windsurf pro Flo Jung has travelled to countless spots in his long career and reveals the best tips on wave selection, timing and stylish turns below.

More tips for windsurfing in the waves:

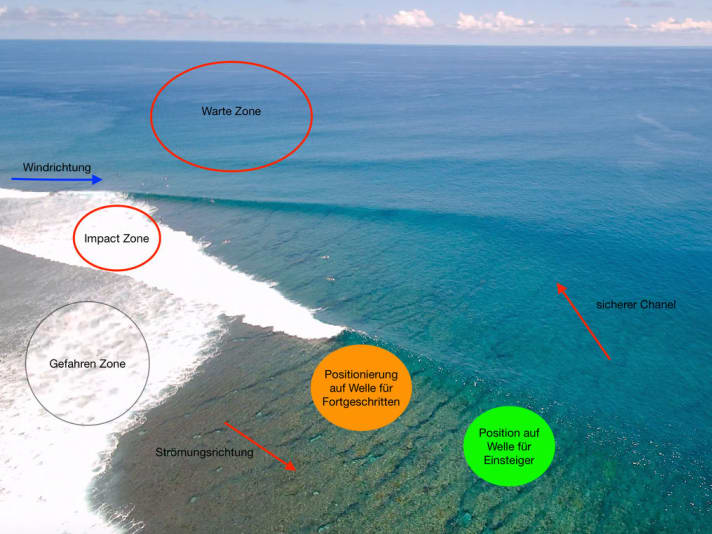

You can always see how different wave spots are in the World Cup. Just because you're the benchmark in Pozo doesn't mean you'll get on in Hookipa - and vice versa. In this respect, pros and hobby surfers feel the same when travelling to a new spot - you have to take some time to orientate yourself when windsurfing in the waves. "Before I go on the water at a new spot for the first time," Flo Jung reveals, "I first take a look at the spot in peace. Where do the waves break? Where can I get in? Are there any dangers such as shallows, rocks or currents? And where can I get ashore if something goes wrong, I get washed up and drift off? In any case, you should observe other surfers and ask about the special features of the spot, as this will help you to relax."

If you're just starting out with wave surfing, it's a good idea to choose a suitable spot. Ultimately, there's no point in putting yourself and others in danger or destroying all your equipment just because you've always dreamed of surfing the heaviest spot. Places with moderate wave heights, sandy and flat entries and sideshore conditions are ideal for less experienced surfers. Spots with very onshore or offshore winds should be avoided at the beginning.

Small wave basics

Waves are caused by the effect of the wind on the water. In "small" bodies of water such as the Baltic Sea, the occurrence of waves is therefore usually linked to the presence of wind. In the ocean, on the other hand, the waves caused by storms often travel hundreds or even thousands of kilometres and then hit the coasts as "ground swell", detached from the local wind phenomena. On their journey, the waves sort themselves out. As the large waves travel faster than the smaller ones, the large waves with a long wave period always reach the coast first when the swell arrives. "A look at the wave period," explains Flo Jung, "reveals a lot about the actual height and quality of the swell. For example, a swell with a predicted height of two metres and a 15-second period (period between waves) has significantly higher and more powerful sets than a swell with a height of three metres and a wave period of ten seconds.

Speaking of sets: Regardless of swell or wind wave, waves of approximately the same height group together. These sets usually come to the coast with three to five waves, and the height of the set waves can often be twice as high as the average wave height. The first and last set waves are often slightly smaller than the centre waves - for wave riders this means: if possible, don't take the first set wave. If you fall, you'll get the rest of the set waves around your ears. It also helps to keep a close eye on the sets when travelling through the surf to avoid an unpleasant encounter on the way out.

The fact that professionals always seem to manage to surf even small waves radically is due to the fact that their experience means they are always positioned at the right point on the wave and also have the right timing. Exactly where "the right point" is also depends on the type of surf wave you are surfing.

Pointbreak

A point break is a wave that does not break along its entire length due to the bottom (e.g. reef), but only at one point. In combination with the right wind direction - sideshore and sideoffshore are ideal - this sometimes results in creamy waves that can run for a long time and allow several turns to leeward. Pointbreak waves have the advantage that they are very easy to read. As the wave always breaks at almost the same point, even wave beginners can approach it slowly. As a windsurfer, the further you stay away from the peak - the part of the wave that piles up the steepest - the rounder the wave shoulder and the safer the ride. The closer you get to the peak, the steeper the wave and the greater the risk of being wiped out in a crash. Flo's tip: "With point breaks, you should first feel your way carefully and, if in doubt, jibe downwind towards the channel out of the wave in good time. As a less experienced wave surfer, you should always approach the peak from the lee side. You should always keep an eye on the peak, because the rule is: whoever had the wave earlier and surfs closer to the peak has right of way over the surfer on the shoulder."

Beachbreak

Beach breaks are waves that break in front of the beach, sorted by size due to the shallow subsoil (e.g. sand) in the water - the larger ones further out, the smaller ones closer to the shore. Most wave spots in Europe are beach breaks. This results in a comparatively unsorted wave pattern with several peaks and a larger white water belt. The size and position of the peaks change depending on the wave height, and a defined channel without breaking waves is usually almost impossible to recognise. Beachbreak waves under 1.5 metres in height often only allow a single turn to leeward before they break over their entire length. Flo Jung explains his tactics: "Many beach breaks are characterised by the fact that there is no long shoulder on which you can place your turns. You often only have the chance of a single turn with power. That's why I position myself upwind of the peak to ride small beach break waves and try to hit the peak on the cutback at the right moment. With the right positioning and timing, you can do really radical turns and even wave manoeuvres like 360s even in small waves."

The more onshore the wind conditions are, the earlier you have to initiate the wave ride in order to arrive at the top of the wave lip at the right moment.

The right timing

Timing a wave ride correctly is no easy task - there is no blueprint for it. Every spot has its own peculiarities and depending on the wind, wave height or tide level, the wave pattern changes even at the same spot within a short period of time. Nevertheless, there are things that can be generalised and that can help you find the right timing. Flo Jung: "In general, the timing at wave spots with cross-offshore winds is completely different to spots with typical "euro conditions", i.e. with sideonshore winds. If the wind blows diagonally offshore, as is the case at many spots in South Africa, Chile, Maui, Cape Verde or Morocco, for example, the wave usually stops for a long time before it breaks. This means that in side-offshore conditions, you can wait much longer before you start your wave ride.

Once you have picked up a wave, position yourself at the peak and stay at the top of the wave. Hit the brakes, look around the front of the mast to leeward and wait until the wave has built up properly. Only then do you pull tight and accelerate," explains Flo.

"In diagonally onshore conditions, I often observe the opposite problem, namely that many surfers start their wave ride too late. The reason: In typical North Sea conditions, it usually takes significantly less time from wave build-up to breaking than in side-offshore conditions. In addition, due to the angle of the wind, you have a longer way to go in onshore conditions to get back up to the lip of the wave when riding frontside.

So the bottom line is: the more onshore the wind conditions are, the earlier you have to initiate the wave ride in order to arrive at the top of the wave lip at the right moment. On the other hand, the stronger the wind blows offshore, the longer you can wait until you start the bottom turn!"

Windsurfing in the waves - tips for riding in sideonshore winds

New moves or not - a smooth wave ride is timeless and always an eye-catcher. Every frontside wave ride can be divided into three phases: The preparation phase with the correct positioning, the bottom turn in the wave trough and the cutback (also known as the top turn).

The typical mistakes when riding waves

Mistake 1: You fall under the sail during the cutback (1a-3a).

The reason for this is that in this case it was obviously not possible to approach the lip of the wave with the sail wide open. As a general rule, the more onshore the wind, the wider the sail must be opened when approaching the cutback. Flo's tip: Keep the sail consistently open with your back hand (1b). Sliding the back hand forwards towards the mast and bending the mast arm will help to open the sail (2b).

Mistake 2: No speed in the bottom turn

Whether it's planing, power jibes or bottom turns - if you tighten your arms and load the board too far back, you'll hit the brakes and stifle your speed (1). Strictly speaking, you can also practise bottom turns on flat water - in the form of cleanly carved power jibes or race jibes. To load the board far forward, the sail pull must be utilised: A wide grip on the boom, the sail pulled tight and stretching the mast arm will automatically cause the sail to build up traction and pull you into the turn with power (2).

Flo Jung also passes on his experience at wave camps: Info is available HERE on the website of the Surf & Action Company.

Manuel Vogel

Editor surf

Manuel Vogel, born in 1981, lives in Kiel and learned to windsurf at the age of six at his father's surf school. In 1997, he completed his training as a windsurfing instructor and worked for over 15 years as a windsurfing instructor in various centers, at Kiel University sports and in the coaching team of the “Young Guns” freestyle camps. He has been part of the surf test team since 2003. After completing his teaching degree in 2013, he followed his heart and started as editor of surf magazine for the test and riding technique sections. Since 2021, he has also been active in wingfoiling - mainly at his home spots on the Baltic Sea or in the waves of Denmark.