Mario Witt is not a windsurfing pro, a product designer or shaper, or any other big name in the windsurfing business. Mario Witt is a chef. Nevertheless, his passion for windsurfing has led to him being recognised by almost the entire World Cup scene.

Every day, Mario stands behind his crêpe iron on the beach promenade in Westerland, his "Crêperie am Meer" is right next to the Hotel Miramar and when he lets his gaze wander over the queue of waiting people, over to the beach chairs and the skuas trying to steal lunch from the tourists, he looks out over the North Sea. Mario has an almost youthful face that laughs a lot. He usually wears jeans and a surf shirt, with an open shirt flapping in the westerly wind. With his baseball cap, which he wears day and night, he looks like a surfer dude in his mid-30s. Only when he takes off his cap, which only happens when he slips into his wetsuit, do his grey temples reveal a glimpse of the decades he has already experienced.

Graham Ezzy has known Mario since he first took part in the Sylt World Cup many years ago - he elicited his exciting story from him.

Mario, at the 2017 World Cup, you and your friend Thommy cooked for the riders in the trendy Shriro Bar. The sushi was amazing and very few people could have afforded it. Why did you do it?

I wanted the World Cup Sylt not to be about merchandising, beer stands and car sales. It's a windsurfing event! I wanted to do something just for the windsurfers.

There is a great deal of idealism in your statements. Was it precisely this idealism that brought you to Sylt back then?

I grew up in the GDR at a time when windsurfing was going through the roof. Because we lived close to the border, we could watch West German television. There was a windsurfing telefitness programme. It was hard to watch something like that and not have access to the sport. There was a series board in the GDR, the Delta, but it cost too much. Life in the GDR wasn't actually expensive, but unfortunately that didn't apply to leisure articles. A Delta cost a few thousand East German marks, the equivalent of about six months' salary. A hairdresser earned maybe 300 East German marks back then, anyone earning 1,000 was already well off. So you had to build it yourself.

How can you imagine the path from a TV series to a self-built board?

My father was a gifted craftsman. He borrowed a Delta board for a week and built a mould. We organised the materials that we thought would work. When the mould was ready, we added glass mats and then expanding foam.

It was often impossible to get hold of the right materials. How did you manage that at all?

If you didn't have a network in the GDR, you were doomed. Everything went according to the motto: "If you have something for me, I have something for you!" The problem was that we didn't have very much - so you had to learn to build things yourself and then trade them again. We knew that we would need polystyrene, so we started by looking for it everywhere. We discovered it in the refrigerated containers of trains. The rest was sourced through relationships around many corners.

How was the maiden voyage?

You bet! I still remember how I could steer the board standing in the straps with my feet and the completely new speed. That's when the fun really began.

In contrast, building a sail was probably comparatively easy, wasn't it?

Where I come from, there was a large athletics centre. We bought a pole from the pole vaulters, which became our mast. The problem was that the pole bent like a semicircle and was far too soft for a windsurfing sail. So we had to come up with something else. My father worked in mining, 800 metres underground. There was a tool for knocking loose stones off the ceiling, and we ended up using one of these as a mast. We built booms from high jump battens and glued the leather from the Wartburg dashboard as a covering. The parts for the mast base came from the lathe and the mums of our surf gang sewed the sails from windbreaker fabric. We made every part ourselves - except for the power joint, which was actually available as a spare part for the Delta in the sports shop.

Did you have access to magazines from the West?

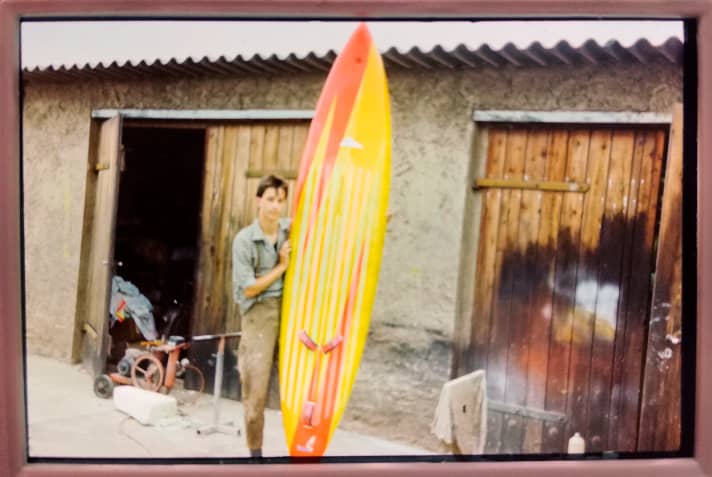

Sometimes you get an old magazine from somewhere. Look here (Mario pulls out an old photo), this is the first funboard I built. I cut out a picture from the surf, projected the board onto the wall in the specified length, copied the outline and built it. I even redesigned the stickers: "Windsurfing Hawaii". The complete board was made in the garage. We often took it to the Müritz, which was the only lake inland where there were waves in strong winds. Surfing on the open Baltic Sea was forbidden at the time because of the risk of escape. Then, fortunately, the Wall came down.

How old were you then?

In 1989, I was just 18 years old and I realised that I had to go to the sea. I knew Jürgen Hönscheid and Sylt from surf magazine. In 1991, I packed my surfing gear into my father's car and drove there with my wife Ivonne.

How did you gain a foothold there?

I had trained as a chef in a hotel in the East, where many visitors from West Germany stayed. That gave me access to a lot of things that you couldn't normally buy in the East. Our life in the GDR wasn't bad, it was a happy time. Nevertheless, like almost everyone in the East, I naturally wanted to "make the move". On Sylt, I immediately had the feeling that I could achieve anything here. I worked as a chef in a restaurant whose owner was also a surfer, and Ivonne worked in service - often twelve hours a day, seven days a week in the beginning.

When I came to Sylt, I realised: Sylt is like the GDR

Doesn't sound like a dream!

Yes, I did, because I spent two hours surfing almost every lunch break and had nice bosses who became friends.

What was your first impression? Sylt is considered to be quite elitist - wasn't it difficult at first as an "Ossi"?

The only thing that was difficult for me was getting through the shorebreak on the water (laughs). Out of ten attempts, I managed once on average. That wasn't a problem in everyday life. Sylt is a bit like the GDR.

What do you mean?

Apart from the fact that I had expected a small fishing village and was surprised at first when I saw the tower blocks in Westerland, everyone was really welcoming. After a few weeks, people were surprised and asked me: "What, you're from the East?" But you were only judged by your work, everyone helped each other without asking for money straight away.

What is it like today?

Of course, the tone has become rougher here, as it probably is everywhere. But there is still solidarity among the locals.

What was it like to suddenly see your idols live on the beach at the World Cup?

The summer before, I got the post and was called up for military service. It started on 1 October. I just thought: "That's not possible, that's when the World Cup starts!" So I didn't go until they sent the military police. As I sat on the train and drove away, I cried my eyes out. After two weeks in the army, I refused to do my military service and came back to Sylt to do my civilian service.

You opened your crêperie in 1998.

I had been selling ice cream from a vendor's tray on the beach for a while and then this shop stood empty. I always wanted to be self-employed and it was a stroke of luck that we got the chance.

On a windless day, it's better not to look for the World Cup riders in the riders' tent or on the beach, but at your place. Why are they all coming?

It has evolved over the years. You've always seen surfers working here - the boards are piled up around the corner. Even today, every employee goes surfing when the conditions are good, if necessary people have to wait longer for their food, but it can't be that there are waves and we can't go surfing. And of course I've also bought a coffee or two for the worldcuppers - simply because I know how difficult it is to get by as a professional windsurfer. But the bottom line is that I think the surfers respect me for my work and that's why they keep coming back. Maybe it's also because the crêperie is a wifi-free zone. People everywhere are just sitting around staring at their smartphones instead of talking to each other, which scares me. People who come to us should eat well, enjoy their coffee, talk and look out to sea.

Looking back, would you do anything differently?

No. (Thinking) Yes, I do! Spending more time with my son. I got married very early and became a father at 22 and I probably spent too much time on the water without considering my family. I still have to apologise to my wife for that today. And because I was so obsessed, I also pushed too hard to get my son surfing.

Is he surfing in the meantime?

The result was that Jason became a great footballer (laughs). He lives in Hamburg, but he knows how to surf and when he's at home and the waves are running, he's on the water.

I assume the name suggestion came from you?

When we were on our way to the hospital, we assumed it was a girl. Then the doctor came: "Congratulations on your son!" We didn't have a name for two days, then I came home and the new surf was on the table. There was a picture of Jason Polakow on the cover. My wife thought it was okay, and that was it...

In 2016, you turned the tables for the first time and accepted the invitation from people like Robby Naish & Co and travelled to Maui. You now really like it there.

Surfing Hookipa for the first time was the only thing missing from my personal surf to-do list. Robby and Victor Fernandez had often offered me the chance to visit them on Maui and it would have been stupid not to do it at some point.

Do you sometimes think it's all a dream? In the past you didn't have the chance to be part of the windsurfing scene, today you're on a first-name basis with everyone and windsurfing icons on Maui provide you with their private equipment.

I could never have imagined it as a little boy. People I used to have as posters on my wall would come to me for dinner and invite me into their homes. Then to be there, the car full of the finest windsurfing, kitesurfing and SUP equipment and surfing every day is incredible. I'm very grateful to the guys for the invitation. But ultimately you realise that they are all just people. Every one of them is approachable and at the end of a long working day they all have the same back pain as everyone else (laughs).

Thank you Mario for the interview!

There is also a webcam in front of Mario's Creperie Am Meer. HERE you can check the conditions directly.