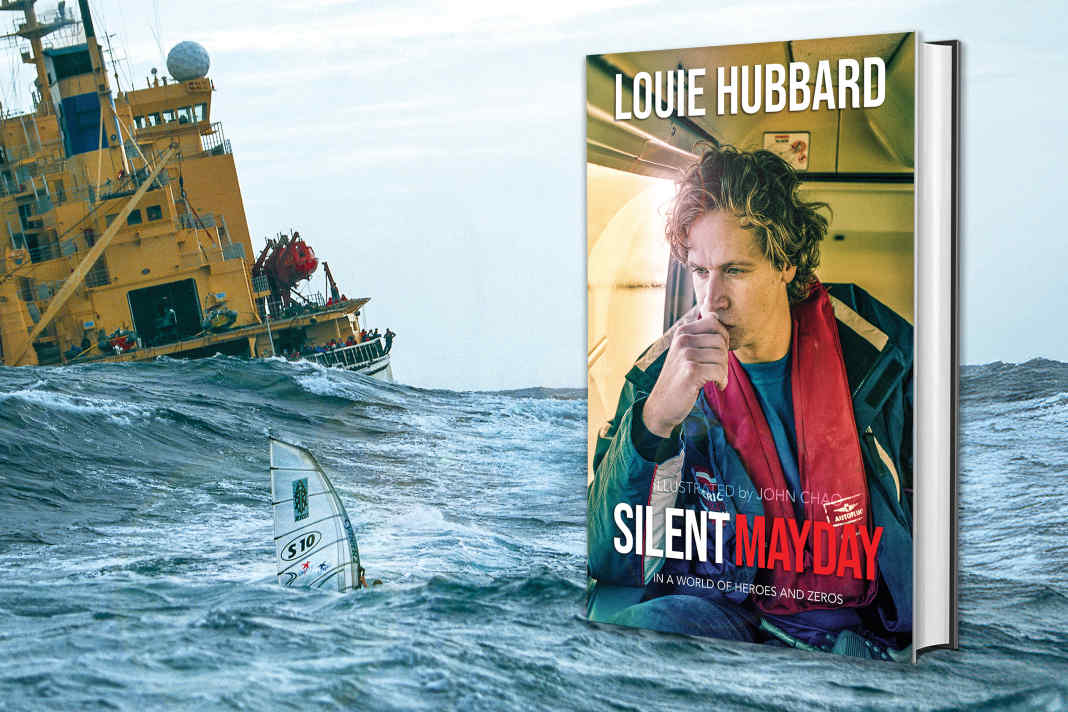

Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race 1998: "The Race shouldn‘t have happened. But it did.“ - Louie Hubbard on the Atlantic race and his book "Silent Mayday"

Tobias Frauen

· 20.06.2025

In 1998, some of the best windsurfers set off for a race all across the Atlantic Ocean, from Newfoundland to the UK. Louie Hubbard was the man behind the Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race, that turned out to be a very important part of his life. Now Hubbard – who also has been PWA tour manager in the late 90s - has written down his story: In „Silent Maydays“ he not only gives a deep inside into the four years of preparation and eight days on the water for the race, but also into his way of dealing with a life-threatening experience and personal trauma.

Your book „Silent Maydays“ wasn’t originally intended just to be about the Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race – you had personal things you needed to write about, and that evolved into the book. Is that right?

Yes, I’d say that’s a fairly good way of putting it. A few years back, I realized I needed to talk about a certain part of my life. The Atlantic races are very much in the middle of it. I needed to express what happened to me before those races, some of which were quite traumatic, and also the things I did afterwards that I never really accepted – that’s where it all comes from. And out of that whole experience, the transatlantic windsurf race was born.

What really triggered the writing, years later, was hearing my son speak. He was 18, and he sounded a bit like me back then. And I thought, “I’ve never talked about any of this.” I couldn’t not be honest anymore. I wrote it, gave it to my wife – said, “This happened. This was my life.” I know nothing about book printing or design, but luckily John Chao does – he made American Windsurfer magazine and was part of the Race back in 1998. He’s put in hundreds of hours, completely unpaid for the love of the sport and to get the story heard.

Sinking on the Atlantic

That traumatic incident was sinking in the middle of the Atlantic with a sailboat, right?

Yes. In 1993, I was a very young captain. I had just turned 21. I’d already been captaining a yacht for about two years – and not a small one either. A 60-foot boat, about 20 meters, which back then was like a 100-footer now. Only millionaires had them. I’d gotten my Yachtmaster certification early, landed a great deal, a great boat, and was loving life. We were doing a return trip across the Atlantic – the same route as the transatlantic race. And it was my third crossing, so I wasn’t a rookie. But we hit a Force 10 storm. That storm took boats and lives. We cracked open the front of the boat and ended up in a seven or eight-hour ordeal that ended with us in a life raft, eventually rescued by another boat.

After being rescued, none of us ever really talked about it. In 1993, people thought the best way to get through something like that was just to forget about it. Move on. But the story of how we sank and got rescued – it's a remarkable story, one that’s really compelling to read. I didn’t start writing about that right away. I wrote other parts of the book first, but I knew I’d have to come back to the storm. And when I did, people were captivated. They couldn’t stop reading. Not just what happened to us out there, but also what was going on back home. We were headline news – all the main British TV stations and newspapers covered it. There was real panic on land.

And that experience, that trauma, led you to the idea of a windsurf race across the Atlantic…

Exactly. When I got back – still only 21 – within a year I was planning a solo windsurf crossing of the Atlantic. And I actually started it twice. Almost nobody knows that. Maybe a few people saw the odd article in Canadian or UK newspapers - I’ve found some of those now. Less than a year after sinking, I left from Newfoundland, Canada, on a solo attempt. Some parts of the preparation were incredibly well done – others were pretty bad. But I was fearless. I didn’t think about it at the time, but looking back, that’s what it was. I thought, “I survived a Force 10 storm. I can do anything.” I had a ton of adrenaline and probably overestimated what I could handle.

I had a ton of adrenaline and probably overestimated what I could handle."

And this is where the book connects to trauma and mental health. Because that year was incredibly tough. I failed in that solo attempt. I’d gone from this young captain, sailing luxury yachts, making good money, surviving the Atlantic… to suddenly being the guy who tried something crazy and failed. I’d spent all my money. I was sitting alone in Canada, thinking: “What the hell do I do now?” That’s where the transatlantic windsurf race really began.

And you felt like you had to bury that first attempt?

Absolutely. I was convinced – and maybe I was right – that if people knew about it, they wouldn’t trust me to organize something like the race. So I pretended it didn’t happen. And that’s hard. Especially as I started moving up quickly. I became PWA tour manager pretty fast, started organizing the race. I became a public figure in the windsurf world. And all the while, I was terrified someone would find out. So the book is very much about the duality: the outward success, and the inward, nervous, scarred person trying to keep it together and not be exposed.

You‘re running a crowdfunding campaign for the book, to raise awareness of those kind of traumas.

Yes, exactly. I thought: if I’m putting this out there, I want it to do some good. So John and I figured out this plan. We’ve raised enough to print a thousand extra copies. So when we go to print, we’ll print however many people ordered, plus a thousand more. Those will go to charities. So we’re hoping to raise £30,000 or £40,000 for trauma and mental health causes.

Is the book aimed more at the windsurfing community or a wider audience?

I think you have to start with your core audience – people who were there or heard about it. So yes, the windsurfing and sailing world. Neil Pryde, for instance, read it – and he loved it. But I hope it grows beyond that. Not just old windsurfers. The windsurf market today is very different – some people don’t even know Robby Naish windsurfed! It’s weird to think. But yeah, we’ll start with the core, and see where it goes.

The PBA became the PWA - and Louie Hubbard became tour manager

What was your original connection to windsurfing? Were you a competitive rider before?

No, I never competed seriously. I took part in some public amateur events—nothing professional. The only races I ever entered were in England, on the Hayling Islands. For me, it was purely recreational. I loved windsurfing—that was my thing—but I only saw it as a passion, not a career path. Sailing, on the other hand, felt more viable professionally. So I went down that road and got into it fairly early. When I eventually stepped into windsurfing from a commercial standpoint, it was about organizing a race. That’s how I first started meeting people in the scene.

Interestingly, I got involved right at the moment the PWA was being formed—right after the PBA fell apart. So my first real connections were with the PBA and Christian Herles. But then everything kind of imploded. For a while, it was chaotic. And then, out of the ashes, the PWA was born.

And did you become PWA tour manager straight away?

Not immediately, but it happened fast. I first connected with Cliff Webb, who used to produce TV coverage for the PBA (and who still does the livestream today, ed.). Cliff introduced me to a few people—Christian Herles from the PBA and Stuart Sawyer, who wasn’t involved with the PWA at that point but was managing a few top riders. So over the next year, I stayed in touch with them while I was pitching the Atlantic race. What’s funny is, things were already starting to fall apart behind the scenes—but I didn’t know that. In that very first meeting with Christian Herles, he was thrilled about my race idea. Told me it was brilliant, that he had sponsors ready, and we started discussing numbers right away. I walked out thinking, “This is it—I’ve done it.” But two weeks later, the whole PBA collapses, and I go from riding high to scrambling.

I went from riding high to scrambling."

I happened to be out in the Canary Islands at the same time the PWA was running its first proper events—Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura, and Tenerife. The organization was having a nightmare. It was a new setup, and the tour and event managers couldn’t cope. One of them quit a few days into the tour. When I flew back to England, Stuart Sawyer happened to be on the same flight, and we got to talking. He already knew about my race project, knew me a bit by then, and at one point he just said, “What about becoming tour manager? Could you do that at the same time?” We had the conversation mid-flight. By the time the Sylt event came around that year, I was tour manager. Cliff was central to all of that. I owe a lot to him.

How long were you tour manager for the PWA?

Five years. At the time, that felt like an eternity. But then Rich Page came in and ended up staying until last season. That’s a hell of a run.

More adventure than competition - how the Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race went

Back to the Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race—can you explain it in a nutshell for those who aren’t familiar?

It was a windsurfing race across the Atlantic, from Canada to England. But to make that happen, we needed teams rather than individuals—no one could do it solo. So it was structured around national teams. We also needed serious logistics: safety vessels, medical support, food, accommodations. That’s how the mothership came in— the russian Icebreaker „Kapitan Khlebnikov“ as a large support ship where everyone could sleep, eat, and coordinate. Then we needed smaller RIBs for immediate support, and even a helicopter for aerial coverage and emergencies. Bit by bit, it turned into this massive floating operation, all to make a transatlantic windsurfing race possible.

What was more important - the adventure or the competition?

In the beginning, it was all about the competition. I wanted the top 20 pros out there, racing flat-out across the Atlantic. But the logistics were so challenging, especially financially, that we had to shift the focus. So gradually, it evolved. The race became more of an epic adventure, a shared achievement. When people look back on it, that’s what they remember. Not just the competition—but the fact that we actually pulled it off.

The race became more of an epic adventure, a shared achievement."

Do you sometimes look back and ask yourself: "Did we really do that?" Especially when you think about the dangers?

All the time. And I ask myself, is that just age talking? Now I think, “Would I really want that responsibility again?” Back then, I didn’t feel that. I felt invincible. That’s how it is—great expeditions are often led by people in their 20s, people with more courage than caution. Yes, there were risks. Getting on and off the mothership from RIBs in rough seas—watching that now gives me chills. But we had good people. The RIB drivers were pros. If someone fell, they’d be pulled out in seconds. But still… I wouldn’t do it again. I’m glad I did, but once was enough.

Do you remember the numbers? How many people, how long, how far did they windsurf?

There were around 70 people involved. The whole thing took eight days. I think we covered about a third to half of the actual distance under sail—because we motored at night for safety and logistical reasons. We had originally planned for more time, but we lost a major sponsor two weeks before the start—$120,000 gone, which was massive in 1998. So we had to shorten everything, renegotiate contracts, and make it work with what we had.

And how did the competition side of it work?

Each team had a dedicated RIB. In the morning, the RIBs would line up to form a start line. The mothership would steam ahead. From its top deck, we had a huge field of vision. Once the RIBs were in position, they’d start the sequence—flags, countdown, the whole thing. The goal was to catch the mothership. It acted as the finish line. Sometimes we’d do multiple segments per day, depending on wind and weather. It was part strategy, part endurance, part wild improvisation. It’s good to look back sometimes and go, “Bloody hell—we actually did that.”

It was part strategy, part endurance, part wild improvisation."

How did you select the riders? Was it just a matter of who wanted to be there, or was there some structured process behind forming the teams?

No, in the end it was open to anyone who had the ability to put a team together. And honestly, that’s where some of the first big challenges started. Initially, I went straight to the professional windsurfing scene. I spoke to athletes, some of whom had managers. Take Björn Dunkerbeck—he was perfect for something like this and would’ve loved it. But he didn’t do anything without a significant paycheck, and we just couldn’t meet those demands. So I went with an idea similar to the big sailing races: raise £50,000, and you’ve got a team. That’s why we ended up with these kind of professional-amateur hybrid teams. Take the Americans, for example: technically amateurs, but incredibly skilled. Eddy Patricalle, Jace Panebianco—these guys were outstanding windsurfers, just not full-time pros. American Windsurfer Magazine got involved, helped pull the funding together. That made it possible.

Speaking of American Windsurfer, you had John Chao on board. He helped you with the book too, right? Was that kind of the PR wing of your operation?

Yeah, sort of. But John wasn’t just the photographer. He owned American Windsurfer Magazine, and when I shifted gears toward allowing amateur teams, I approached him and said, “What about an American one?” He jumped on it. He managed the whole thing: built the team, handled publicity, organized logistics. He came on the mothership too, doing about five jobs at once—absolutely essential. He was unique in that he had a mindset similar to mine: “Let’s just make it happen.” No endless questioning—just action. That’s rare. And when I started writing the book, it was instinct to reach out to him. He’s got every photo from that time. He was happy to see those pictures used again. It all came full circle.

How a credit card saved the race at the last second

Looking back, what’s your fondest memory from the race—and the worst?

The sweetest moment? That’s easy. It was when we finally got the green light from the weather and actually made the race happen under those extreme conditions. There were real doubts about whether we could pull it off. Not from the windsurfers so much, but from the support crew. There was a clear hierarchy on the boat, and we needed to convince the RIB drivers. When we got those RIBs into the water and you heard the reactions from guys like Robert and Anders afterward—“I’ve never done anything like that before”—you knew we’d done something extraordinary. Not just a race. It was an event. Something historic. That moment made all the stress and smashed equipment worth it.

We had done something extraordinary. Not just a race. It was an event. Something historic"

Now, the worst? Honestly, it was a financial nightmare. The night before we left, I realized I’d made a serious miscalculation. I had agreed to pay port costs for the mothership, assuming one night. That would’ve been around $4–5K. But delays meant the boat was docked for three nights, and then other costs added up. When I went to the harbourmaster for the bill, it was $12,000. The boat wouldn’t leave until the payment cleared. In the end, it was my American Express card that saved the race. Back then, Amex didn’t have a spending limit. I called them, said I was on holiday and needed to charter a boat for $8K. They approved it. It was so stressful. The race truly shouldn’t have happened. But it did.

When you see today’s tech—drones, social media, livestreams—do you ever think, “Damn, I wish we had that back then”?

Oh, totally, 100%. This event happened 27 years ago, and still no one’s done anything like it again. I never expected that. Normally, with action sports, things get more extreme over time. But even today, people look back at our race and say, “Wow.” If we did it today—with drones, live streams from the mothership, on-board social—you could create something phenomenal. If I could do it again, I absolutely would. With today's tech, you’d have people watching and saying, “Have you seen what they’re doing out there?”

When you sat down to write the book, did all these memories come rushing back? Or had the Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race been with you all these years?

Yeah… it’s funny. Not deliberately, but I had drifted away from a lot of those people. Life happened—kids, moving countries,different jobs. But writing the book reconnected me with so many of them. People from before the race too—like those I was with in the liferaft when our boat sank. Or the solo attempt I made later. So now, as I reach out to everyone again, I’m saying, “Hey, remember that time? Well, here’s what was really going on behind the scenes.” The responses have been incredible. It’s been the best part of the whole process!

Thank you very much for the interview and good luck with the book!

Trans Atlantic Windsurf Race - the documentary

Tobias Frauen

Editor