There are people who walk straight from the beach with wet feet and dishevelled hair to the surf shop, 100 metres from the beach, to check on the internet whether there is enough wind for surfing. An anecdote that shop employee Frank Lewisch from Lake Neusiedl likes to tell. What seems unimaginable to him as an old hand, perhaps plagues more windsurfers than you might think.

After all, not everyone can read from nature what the classic Beaufort scale indicates: Whether "thick branches move" (wind force six) or "trees sway" (wind force seven) was perhaps clear to Francis Beaufort in the 18th century. Today, we prefer the hard, measurable currency for wind: in knots or metres per second. Just as we know it from the forecasts of Windfinder & Co. Windsurfers like Frank look at the water and know which sail is right for them. This has been trained in thousands of surfing sessions. The brain automatically takes into account the wind direction, possible cover on land, wave height and incidence of light. All of this can deceive the senses and requires an infinite amount of experience. And that's why many surfers still like to use an anemometer, even if it's just to make sure they don't set up the wrong sail unnecessarily. Because the measuring devices differ significantly in terms of price and accuracy, we have had an independent test carried out in a specialised wind tunnel as a joint project by surf and Kite magazines. The result was that you don't necessarily have to spend too much money for good measurements.

Body influences measurement result

The test in the wind tunnel also showed that the devices are not the only source of errors. Body posture during the measurement is also reflected in the measured values. Depending on the device, the display fluctuates depending on whether you are standing straight or at an angle to the wind - even if the device is held upwards. With the Eolo1 from Skywatch, this difference was over 20 per cent. The reason for this is that if the body is facing straight into the wind, it creates a windward draft that is included in the measurement. However, if the body is turned sideways to the wind, the wind can pass more easily - the sensors are less affected.

With impellers, you have to know which way the wind is blowing

The anemometers tested - also known as anemometers - measure the wind using mechanical rotating constructions. While cup anemometers capture the wind with small blades and rotate horizontally, vane anemometers are fitted with small impellers that rotate like small windmills. The disadvantage of vane anemometers: They must be held directly in the direction of the wind to avoid being blown at an angle. On the Windmate 100 model, a small wind vane therefore indicates the direction of the wind so that the device can be correctly aligned. Other manufacturers rely on the maximum value method to eliminate the error: The device should move through the wind window by swivelling horizontally. The maximum value then shows the actual wind speed - or so the theory goes. However, gusts of wind are not taken into account with this method - so this measurement variant is hardly suitable for practical use.

Rotations can also interfere with shell cross knives

In the wind tunnel, a misjudgement of the wind direction was simulated by rotating the measuring devices by 20 degrees. Our assumption before the test: The cup anemometer should not be affected by this effect, while the impellers of the vane anemometers should react more sensitively to it. The vane variants, above all the Xplorer from Skywatch, did indeed react to the rotation in a clearly detectable way, but the Eolo1 cup-and-cross system also reacted to the horizontal swing, which is probably due to a change in the aerodynamics on the underside of the device. Curiously, the error due to the rotation even compensates somewhat for the generally too high display of some devices, but this remains incalculable in practice. The other cup anemometers, which also include the fixed weather stations, showed little or no susceptibility to wind direction.

You can find the entire article as a PDF download below.

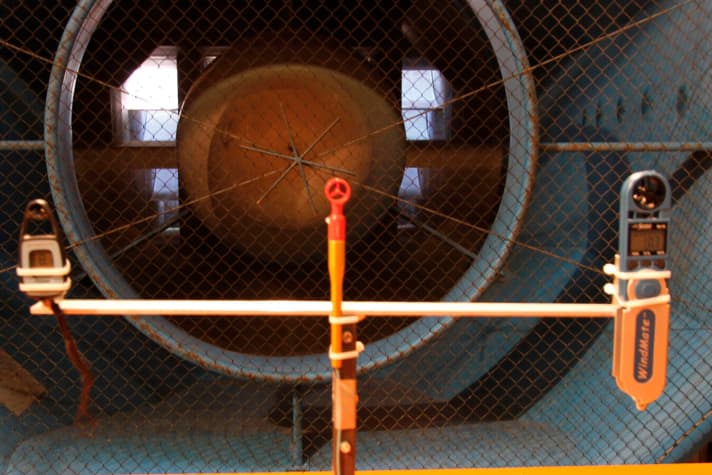

The test set-up in the GST wind tunnel in Immenstaad on Lake Constance: the test candidates on the left and right, with the reference anemometer in the centre measuring the actual wind speed.

Trendsetters no longer hold their anemometer up to the wind, but their iPhone and smile at the old-school beaufortists. We wanted to know: Can the iPhone's microphone deliver accurate readings? First surprise: the iPhone didn't like the noise of the wind tunnel turbine and displayed wild readings. So we learnt: The app requires natural wind. We took a small wind test on the beach in winds between one and six knots. We pressed "Get Wind", then the thing should measure. If you press "Got Wind", you should get the average speed. However, the results in the lowest wind range were pure coincidence and had less in common with the results of the Windmaster 2 than the subjective Beaufort feeling with the real wind. Conclusion: In the lowest wind range, our app was a flop.