Every windsurfer who lived through the 80s and 90s knows his pictures and films. However, only very few people were aware of Jonathan Weston. His job was to show the world through pictures how great windsurfing is. In recent years, he has put a lot of work into the "Windsurfing Hall of Fame" and maintains it with great attention to detail.

Jonathan, the windsurfing hype of the 80s washed you from California to Hawaii, where you became one of the first water photographers and filmmakers, and from there back to a lake in Sacramento. So it's a long story, where do you start?

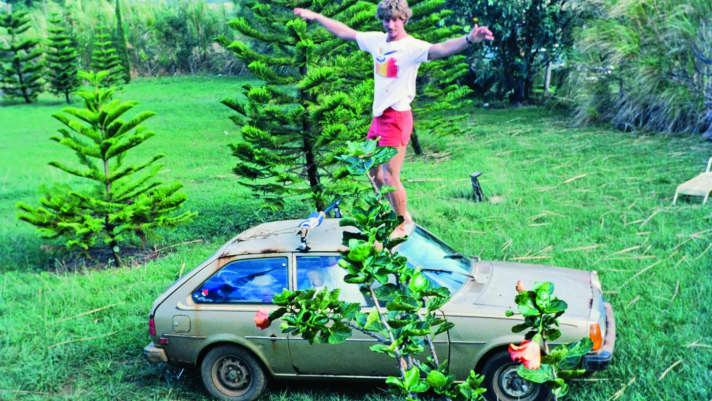

Preferably right at the front. I had started studying at a photography school in Santa Barbara/California in the 70s, but when I was quite successful in a few regattas and windsurfing became a bigger and bigger part of my life, I dropped out. Like everyone back then, I dreamed of Hawaii. In 1980, I packed up my self-built board and set off for Oahu for the first time. The beginnings there were wild. I bought a car for 200 dollars - no, it was more of a moving wreck - which took me to the beach and served as my sleeping place at the beginning. You quickly got to know people, lived in their garden and slept on the terrace. Nobody had any money in their pockets. If you found some small change under the seat in the car, it was a great joy. All that mattered was going windsurfing every day, nothing else.

At some point I needed some raw materials to shape a new board and ended up at the Town & Country Surfboards factory in Pearl City/Oahu. At the time, there was a growing demand for windsurf boards from surfboard manufacturers, as windsurfing was the fastest growing sport in the world. The owner of the workshop, Craig Sugihara, said: "Bring your board round when it's ready. If it looks good, we need to talk." A short time later I had a job as a shaper.

The best pictures of Jonathan Weston:

In the early 80s, all the windsurfing pioneers first landed on Oahu. Why?

At that time, material development had not yet progressed very far. Moderate winds were an advantage, so Oahu was ideal. And it was the time when Robby Naish, who grew up on Oahu, dominated the scene, which had a certain pull effect. Maui, on the other hand, was initially uninteresting: it was too windy and also completely underdeveloped at the time, the island was completely left behind economically - nobody wanted to go there voluntarily. One day I was standing in the workshop with my boss Craig and showed him my latest board creation, a very short board with a wide tail and bat wings. 'Looks like Batman's car,' said my boss. 'A guy from Maui is coming round soon and if you keep building boards like that, I might give him your job. The "guy" was Malte Simmer (later founder of the sailing brand Simmer Style, the ed.) and built even wilder things than me - Batman's car on steroids, so to speak.

Did he get your job?

Fortunately not. But he showed me pictures of Maui for the first time. It was like brainwashing for me. There were a few guys surfing high waves and jumping metres into the air. But it would be a while before I made the leap from Oahu to Maui.

In 1981, Robby Naish was already the hero of the sport. Do you remember the first time you met him?

I still remember it well. He was already a superstar back then. When he went out on the water at Diamond Head (the most famous wave spot on Oahu, the ed.), he usually took off from his girlfriend's garden, whose parents had a house there. He rarely mingled with us mortals on the beach. He always had an entourage around him, they rigged his stuff. When everything was ready, he would surf out, fly through the air, catch a wave and rip it into pieces. For a long time I wondered if he could even waterstart because he never crashed. Back then, the windsurfing world consisted of Robby Naish, then nothing for a long time and then at some point people like Mickey Eskimo or Pete Cabrinha (later founder of the kite brand Cabrinha, the ed.), who grew up to become world-class surfers on Oahu in Robby's shadow.

A photo legend as inspiration

How did you make the transition from life artist and shaper to photography?

Back then, I developed a kind of love-hate relationship with a guy who packed the boards in our factory, his name was Warren Bolster. He was a pretty down-and-out surfer and skater who hardly liked windsurfing but gave me a lot of food for thought with his provocative questions about my shape creations. It took me a while to realise who was actually doing the dirty work in our camp: I got my hands on an old skateboarder magazine and discovered the copyright "Bolster" on many of the pictures.

It turned out that Warren was a photography legend, because as a photographer and editor of the magazine he had brought the dead sport of skating back into the consciousness of young people by portraying the legendary surf skate gang Dogtown and Z-Boys. Since then, skating has gone through the roof. Unfortunately, he had pretty much fallen off. At some point I took him to Diamond Head and he threw himself into the break with a water camera. My boss had to look for a new warehouse worker pretty quickly. And that also rekindled my love of photography. But before that happened, a few things went wrong...

In what way?

I had already quit my job at the shape workshop because I had been offered a job at Sailboarder, one of the big windsurfing magazines at the time. It sounded like a sure thing, but it went wrong. I stood on the street, leafed through the Yellow Pages and finally applied to UP Sports, who were building kites and sails at the time and also wanted to offer their own windsurfing boards. The condition at the time was that I would get the job as a shaper if I made it into the top 10 at the renowned Hang Ten event. Fortunately, that worked out. And I convinced my boss that I had to go to Maui to be closer to the scene.

Maui was anything but a paradise

Maui is still considered "the place to be" in windsurfing today, but it's also a place where the going gets tough. What was it like back then?

I came there with Pete Cabrinha in 1981. It was a tough school even back then, in many ways. During my surf session in Hookipa, I ended up on the rocks and destroyed my equipment. The spot was dominated by surfers and defended to the death. Five or more surfers at the break meant that windsurfers were better off staying on the beach. And there were windsurfers there, like Mike Waltze, who didn't want the spot to become increasingly popular. But it couldn't be suppressed.

What was it like in the days when milk and honey supposedly flowed and everyone could get good sponsors?

In the early days - we're still talking about the early 80s here - it wasn't easy at all. There was Robby Naish, he was the king. And then came the rest. I personally couldn't complain, I had a good sponsor back then in UP Sports. In 1982, I asked my boss for money to pay a hospital bill. I had been run over in Hookipa and hit my head on the bow of a surfer. My boss thought about it for a moment and told me that he would do me a favour now: kick me out! He obviously thought I'd had it too easy so far and needed to work hard to discover my talents. So he gave me the boot, even though we had a really good and friendly relationship. I was horrified at the time, but looking back he was of course right. This experience finally got me into photography and film.

Film and photography was a completely different approach back then than it is today...

Absolutely. I ordered a water housing. On the first day, I put the camera in, swam into the line-up in Hookipa, looked through the viewfinder and saw that my housing was full to the top (laughs).

Obviously you got your act together afterwards...

I had to get by for a long time with part-time jobs until I could afford a new housing, oh boy. But the first roll of film that I developed already had it all. There were pictures by Mike Waltze, Fred Haywood and Matt Schweitzer that had never been seen before.

Mike Waltze was not pleased

You're talking about some of the biggest personalities in sport. Were they your buddies back then? Or did you just have to photograph the guys if you wanted the best pictures?

The hard core of Maui surfers was still small back then, of course everyone knew everyone else. Some were friends, others not so much. Mike Waltze was the top dog and was actually quite angry with me because of an article I had once published in a magazine. It was about the fights between windsurfers and surfers on Oahu. I ended the article with the words: "Move to Maui, I did!" According to Waltze, this had triggered a run on Maui.

Did revenge follow during your first photo session in the water?

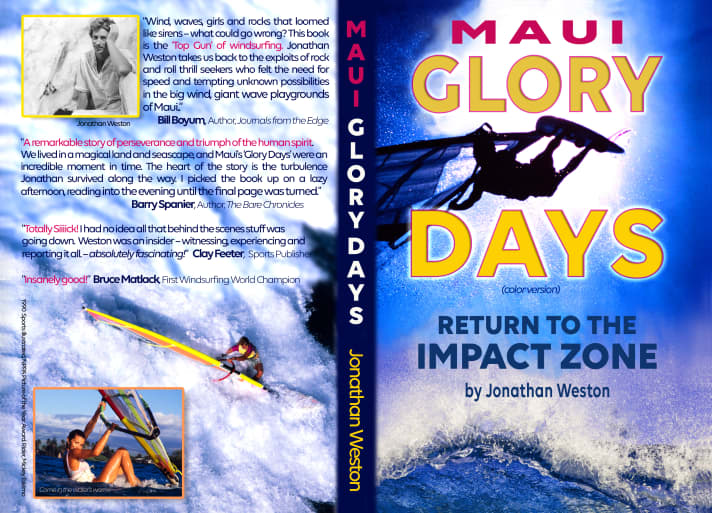

When I was in the line-up for the first time, Waltze came racing towards me. I was sure he was going to knock my head off. Ironically, the picture that was taken ended up on the cover of my book.

What was so groundbreakingly different about your pictures back then?

I was the first photographer to move directly into the Hookipa impact zone with my camera. Erik Aeder joined me just under a year later, but at the beginning I had the spot to myself, which was fantastic. I wanted to show the world how great windsurfing is, and that was only possible through photos and clips. But the real breakthrough came with the first helmet camera.

Jonathan Weston, the first surf film maker?

We're probably not talking about GoPro format here?

No, not really. The thing was so heavy, I can hardly believe I didn't break my neck (laughs). We did the first tests in secret and went to Sprecks (a spot a few kilometres southwest of Hookipa, the ed.) for the test shots, where nobody was at the time. We had 15 seconds of film, but the cameras at the time couldn't cope with the vibrations of the landings and all we could see was noise. So it was clear that I could only drive straight ahead to follow other drivers. But even then, I usually only got 30 to 45 seconds of usable footage. Most of the time was spent swapping tapes, mounting everything, licking lenses clean to let the annoying water droplets roll off. But even these short snippets of film were enough to see what was possible and open doors with sponsors. It's frightening that in the age of modern action cams, many people still don't understand how to take good pictures.

What is your specific tip?

Good shots are not made by filming yourself, but by filming each other. Instead of strapping an action cam to your top, it's better to put it on a helmet and follow and film each other. That was also the recipe for success for my first film "Impact Zone".

You also worked a lot with Mickey Eskimo back then, who was always controversial because of his productions. How did you feel about working with him?

Mickey was simply incredibly creative. His graphics adorned the boards of various brands and he did everything he could to get a good shot. He didn't care whether he stood the move or not, as long as the photo turned out well. This brought him a lot of headwind in the scene, but ultimately he was extremely successful with his creative style. Although he only won a few heats, he had over 200 cover shots in windsurfing magazines worldwide and sponsors such as Windsurfing Chiemsee. It was the time when windsurfing became sexy and you could fill several halls with windsurfing stuff at boot Düsseldorf.

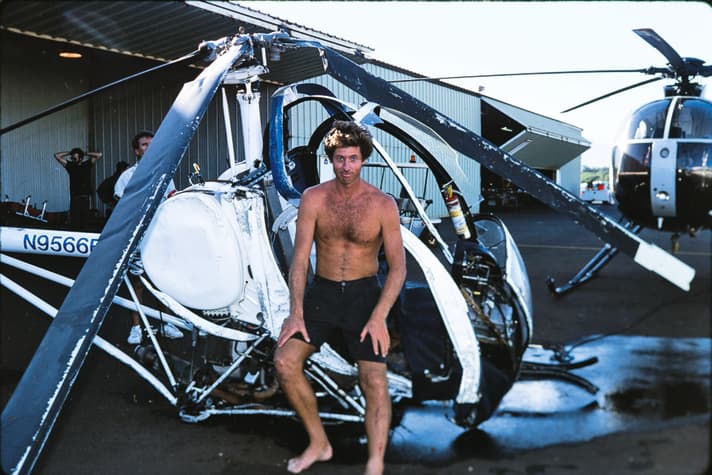

Years later, Mickey also set up a film project with Chiemsee called "Double or Nothing" with Jason Prior and Francisco Goya. This film had a script for the first time and was supposed to combine drama and comedy elements - if you shared the idiosyncratic sense of humour - and of course offer solid action - in case the acting and humour thing didn't go down so well. It all went great - unfortunately I crashed the helicopter just before the end of filming.

The legendary helicopter crash at Spreckelsville

The picture of the crashed helicopter in the Spreckelsville line-up went around the world. What happened back then?

I had filmed from a helicopter before and knew that it wasn't 100 per cent safe. That's why I was happy to work with a well-known pilot. He had screwed up a lot in his life and instead of going to prison, he had to do reconnaissance flights to clear out illegal marijuana plantations as a public service. So he was good at flying in rough terrain. That day, however, another pilot I didn't know had to step in. But it was all arranged, so I had no choice. I hung out on the side of the helicopter with the camera in my hand and filmed. The new guy didn't lack courage, but he did lack control. Once he almost sabred Robby Seeger's head off. It was adventurous. I said: Let's call it a day! We flew over Sprecks towards the landing site and waited for permission from the tower, when I spotted Jason Prior surfing there. Jason should have been on the water in Hookipa by now, he was one of my main protagonists after all - but as usual he was late and a bit of a schedule warp. I took the opportunity to take a few last shots of him when I saw a very strong gust approaching. The gust pulled the helicopter up, turned it on its side and it nosedived sideways towards the surface. I tried to jump out but forgot that I was strapped in.

When the rotors hit the water, it was the loudest sound I've ever heard. Everything was silent for three seconds, the pilot and I looked at each other briefly and a few moments later we were underwater. The helicopter was on the reef. I could see the surface above me, but I couldn't get one of the two safety harnesses open. I was underwater for a long time, I estimate about two minutes. Luckily I had horse lung at the time. When I had freed myself, I managed to surface briefly, but the camera with the heavy battery pack pulled me back down. Somehow it didn't occur to me at the time to let go of the camera. I disconnected all the batteries underwater and was finally able to surface. It was very lucky that I survived with only minor injuries. Nevertheless, it was impossible to think about finishing the film in time.

You filmed all the icons of the scene, who stuck in your mind?

Mark Angulo and Jason Polakow. In their day, they were simply unique in terms of their creativity on the water. Everything they did looked lighter, as if they were floating. Robby Naish was equally impressive, but he was always better downwind. Mark Angulo was probably the most talented of them all.

For the Angulo brothers Mark and Josh, fame wasn't all good news...

Mark could have won everything, but unfortunately creative people aren't always the most professional. Jason Polakov was different, he was more professional and never went off the rails. His problem was the constant injuries. I think there's hardly a bone that doesn't have a screw in it. If he had been less injured, he could have dominated windsurfing even more. On the other hand, his way of surfing would simply not have been possible without injuries.

What were you back then - creative or professional?

To a certain extent, I share the fate of the creatives. I loved photography, but I actually always wanted to get out on the water myself, which of course meant that my work suffered and other photographers like Erik Aeder or Darrell Wong came along and landed big deals with major brands.

Why did you end up turning your back on the island you had dreamed of for so long?

At some point, other things were more important. For example, my daughter's education and Maui was simply not a good place for her. I left there in 2000. I closed this chapter for myself with my book ( available here at Amazon )

Do you get a lot of feedback from the legends of the scene, who have presumably all read it?

Little. Most of the protagonists don't want to read it, they don't want to look back. But I get a lot of praise from people who are normal windsurfers and who like to look back and soak up the stories. It shows the life that many people would have liked to have had back then. But unfortunately Hawaii remained just a dream for most of them.

This interview first appeared in surf 6/2020.

Manuel Vogel

Editor surf

Manuel Vogel, born in 1981, lives in Kiel and learned to windsurf at the age of six at his father's surf school. In 1997, he completed his training as a windsurfing instructor and worked for over 15 years as a windsurfing instructor in various centers, at Kiel University sports and in the coaching team of the “Young Guns” freestyle camps. He has been part of the surf test team since 2003. After completing his teaching degree in 2013, he followed his heart and started as editor of surf magazine for the test and riding technique sections. Since 2021, he has also been active in wingfoiling - mainly at his home spots on the Baltic Sea or in the waves of Denmark.